Project outline:CUT/STACK/BURN is a performative re-enactment of a redundant rural activity - furze cutting for domestic fuel (or gorse outside of cornwall). The project uses art installation as a platform to develop a visual conversation about the implications and absence of sustainable approaches in the management of land and its resources. Our current use of energy in an age of climate change becomes a focal point and pivotal issue in this visual debate.

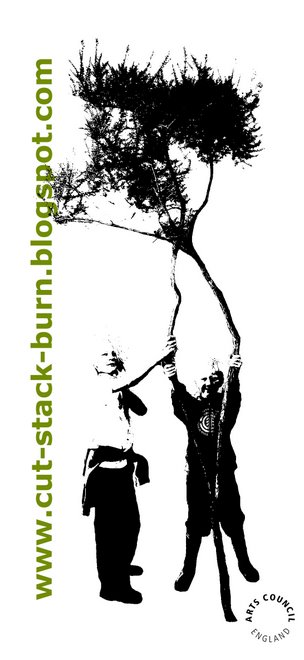

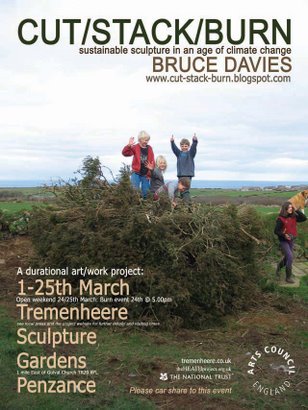

event poster

Sunday, 29 April 2007

CUT/STACK/BURN - the video

I have alot to do before I'll be able to show the video footage I took but in the meantime you can see Rupert Whites' youtube video at http://www.artcornwall.co.uk/ in the exhibition section. It is a good document and captures the various elements well. Thanks to everybody who helped me achieve what I did, those who have followed the plot thus far and those turned out to see the final stage...your response was amazing...the following posts are odd notes and scribbles form my journal...best wishes...Bruce Davies

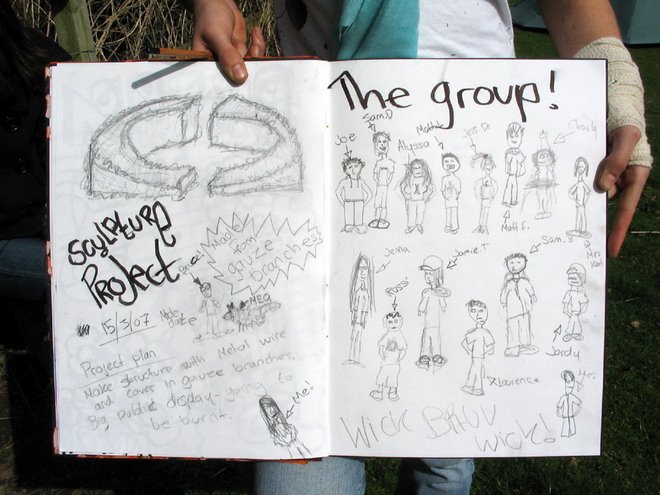

I did one project presentation in school all the rest were on site at Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens. These in-situ presentations at the gardens allowed for a more discursive engagement whilst the presentation at St just primary in front of the whole school (220 children) allowed me to develop the social historical theme and the context of the art work more in depth. I demonstrated how to make ‘poor man’s Holly’ [see blog site for details] using various teaching aids such as furze flour and berries by involving the children but also power point presentations showing old photographs of furze management, the references that I used to develop the sculptural form of the art work, the progression of the cutting and stacking accomplished by the project so far and sketches of the work that y6 would go on to help create.

The involvement of school children in the workshop sessions was a successful and rewarding process - 60 participated in total. They children engaged with the task of constructing the work with enthusiasm and good humour. They weren’t deterred by the laborious nature of the task and took part with gusto, taking a lot of pride in the quality work that they produced.

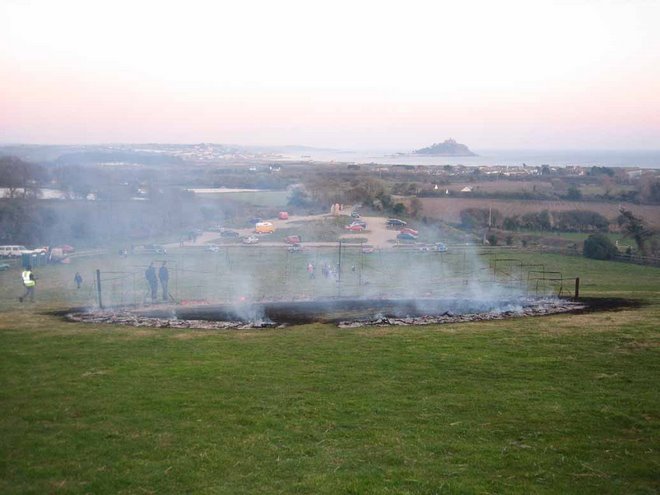

afterburn...

A group of about 10 hardy stalwarts stayed on after dark. It was like a private view but in reverse - bottle of bubbly, pizza all round. As we munched and mulled over the event inside the ash circle a light breeze would waft the embers and it would glow briefly and then die down again. Later a 4ft tornado of sparks momentarily whirled suddenly between the remnants of the steel supports and worked its way along over the ashes picking up sparks as it went before finally petering out.

The work was lit from below the green furze fire break at exactly 6.00pm after contacting fire control. I worked my way slowly round toward the right. I was calm and unworried; in fact I was more concerned about Nigel Cook, the National Trust warden helping me light it, as he worked the left side. He was more likely to get roasted as the breeze was in his direction. I had been so focused on the construction and project development my thoughts about it when on fire hadn’t really emerged. As it turned out I couldn’t see it as it initially went up in flames as each time I lit a new section I had to quickly move on. I had hoped to have lit it as a complete ring but it took ferociously quickly that I had to light it at sections spaced a couple of metres apart. Shouts from the crowd telling me ‘to get on with it’ perturbed me not as I knew from previous experience it would ‘go like stink’ though how long it would last was debatable. I wasn’t disappointed. The major part of the burn was over in about 10 minutes. The colour of the flames was a surprise. I have never seen or imagined such an orange. At one point at the height of the fire I saw a tornado of flame appear briefly in the centre of the work no doubt due to the shape of the construction and swirling rising heat. Dave Slater whose green furze filled the fire break worked out that the flames reached a height of over 60 feet. I drew the same conclusion on examining the photo records a few days later. A sense of euphoria kicked in as the applause came from the crowd and I stood back to witness the destruction. It is only now am I getting a sense of some kind of loss. I miss it now. What a waste…

There were many opportunities to expand the event into a bigger event with additions such as projections/music/food/bar etc but I felt that a more austere event was more appropriate and in keeping with the concepts behind the work. So on the day the audience had only themselves, the gardens and the work to interact with. It was just the right kind of pitch.

It could have been so different considering the changeable nature of weather patterns around that time of year. As it was people were relaxed and children played. I had experienced deluges of rain on many occasions while gathering the furze. One time in February I was out at Coverack and got so wet I had to change before driving home but before I had managed to get into the car the dry clothes were almost as wet. Later in March I got sun burnt one day and the next day it snowed sleet and was bitterly cold. Later the same day I was back to wearing a t-shirt again.

The site was a spectacular setting to present a large scale environmental work which was further enhanced by the superb weather on the day of the burn. A cloudless sky and strong sunlight all day from sunrise to sunset. With no wind, just a slight breeze, it meant that the work could be viewed from almost 360 degrees. The fire safety officer had suggested that I increase the barrier from 25m exclusion zone to 30m. This I did and most thought - prior to the burn - that it was a bit excessive. After the burn however people commentated on how intense the heat was with some concern for camera equipment expressed. Had it been 5m nearer it would have been very uncomfortable.

It is interesting how the use of a landscape can change when one use takes precedence over another. On my first visit to the site last October I noticed spent shotgun cartridges lying around in the grass at the top of the field. When camping at the site on night watch duty people would arrive almost nightly to go lamping for rabbits around the gardens perimeter. But they didn’t come into the field that I was in. The first night after the burn they were back - notable by the evidence left there in the form of shiny new spent shotgun cartridges. The scorched earth has now been reclaimed by rabbits ants and beetles. Rabbit droppings and tracks are traceable along its complete curve. I discovered a fox stool on the circular burn mark with evidence of rabbit in it. It has become quite a battle ground.

Two weeks before the burn I decided I could no longer leave the work unattended from early evening and began to camp out in a tent. This was most the wobbly part of the project as it meant time away from home and family. I don’t think it would have looked very good if I had received a phone call in the middle of the night in my own bed telling me someone had set it alight. An interesting point about this was the concern other people were showing in and about the work. As I was on site from early morning to dusk I could see when people mostly used the site and who, so it didn’t really strike me as much of a concern. The gardens is 3 miles from Penzance and a mile from the nearest village, though other people thought my presence absolutely necessary. It was quite touching in a way. The biggest danger I felt was people shooting rabbits at night - hot lead and tinder dry gorse didn’t sound like a good recipe.

Hard won energy - working with the material

It bites! Long leather rigger gloves helped protect the wrists with another smaller pair worn underneath to limit most of the more persistent needles. Removing them from your hands and legs was a daily occurrence with some causing infections fairly quickly if not removed. Some were impossible to remove and I’m still finding them now. Handling by the stem was the way. The larger bushes had to be reduced in size by pulling the branch away from the stem. It was cut mainly with machete but also loppers and bow saw.

The first crop of furze cut for the project by the National Trust was at Coverack [the other sites were Kelynack, St Just, Morvah, Gulval, and Tolver]. This presented two problems for me. One I didn’t really know how much material I actually needed. Furze hasn’t been used in a construction for over 30 years that I know of and possibly longer elsewhere. There was no one to tell me how to do it. I had to rely on my skills learnt as a dry stone waller/stone hedger to visually quantify the amount. This also meant I had to take anything that would bundle up into a faggot. I couldn’t afford to leave some behind because it was a bit too twisted or the like. This meant that when I came to carry them by hand some where too heavy to lift. Also as the furze had been cut it had been unceremoniously dumped in large piles and had consequently become tangled up and difficult to separate. In the past the would have been laid out with a thought to how it would be handled next in the faggot making process thus making it more time and cost effective.

Instances like this, when material handling for example, really brings a sense of its historical context to life. You start to get a feeling about how they would have done things - and how they wouldn’t. The next cutting that took place was done in a much more orderly way. Each compartment of cut furze was laid out in lines so that when it came to laying them out for tying it became a quick and efficient practice. The massive volume of material that was eventually needed [3 full silage trailers loaded and pulled by tractor] inspired all kinds of would be solutions to improve on the old technique of bundling into a faggot and tying with twine. Some ideas required compressing an overly large mass of furze with the winch of a Landrover but this just snapped the branches. Another was to use ratchet straps to act in a similar way but this again failed miserably in comparison to a natural fibre twine as the excess of the strap needed to encompass the faggot was too unwieldy once it had come under compression. The most successful way of creating a faggot was to lay a 3m line of twine on the ground. Lay the required amount of furze on top of this, which as a general rule stood about 1.5m off the ground. This part of the process was an adaptation of the traditional method of faggot making. It was necessary to reduce the overall mass of the material to reduce transport and environmental costs. Traditionally the furze was cut in a manageable armful and then tied with a green whip, possibly goat willow, perhaps in a similar style to how a bundle of willow rods are tied. My adaptation meant laying the fuzz outward at both ends to balance the shape to create a more symmetrical faggot. [This change to the dynamics of the traditional faggot was the main concession to the modern age the project made other than that of transportation]. A loop was tied at the end of the twine drawing the other end through. As the faggot tightened at the pull of the twine I placed my boot onto it to help shape and round of the faggot and to compress it further. Creating a tightly formed well shaped faggot was a really satisfying process. The ideal size and weight of the faggot being determined by whether or not it could be carried by one person.

It bites! Long leather rigger gloves helped protect the wrists with another smaller pair worn underneath to limit most of the more persistent needles. Removing them from your hands and legs was a daily occurrence with some causing infections fairly quickly if not removed. Some were impossible to remove and I’m still finding them now. Handling by the stem was the way. The larger bushes had to be reduced in size by pulling the branch away from the stem. It was cut mainly with machete but also loppers and bow saw.

The first crop of furze cut for the project by the National Trust was at Coverack [the other sites were Kelynack, St Just, Morvah, Gulval, and Tolver]. This presented two problems for me. One I didn’t really know how much material I actually needed. Furze hasn’t been used in a construction for over 30 years that I know of and possibly longer elsewhere. There was no one to tell me how to do it. I had to rely on my skills learnt as a dry stone waller/stone hedger to visually quantify the amount. This also meant I had to take anything that would bundle up into a faggot. I couldn’t afford to leave some behind because it was a bit too twisted or the like. This meant that when I came to carry them by hand some where too heavy to lift. Also as the furze had been cut it had been unceremoniously dumped in large piles and had consequently become tangled up and difficult to separate. In the past the would have been laid out with a thought to how it would be handled next in the faggot making process thus making it more time and cost effective.

Instances like this, when material handling for example, really brings a sense of its historical context to life. You start to get a feeling about how they would have done things - and how they wouldn’t. The next cutting that took place was done in a much more orderly way. Each compartment of cut furze was laid out in lines so that when it came to laying them out for tying it became a quick and efficient practice. The massive volume of material that was eventually needed [3 full silage trailers loaded and pulled by tractor] inspired all kinds of would be solutions to improve on the old technique of bundling into a faggot and tying with twine. Some ideas required compressing an overly large mass of furze with the winch of a Landrover but this just snapped the branches. Another was to use ratchet straps to act in a similar way but this again failed miserably in comparison to a natural fibre twine as the excess of the strap needed to encompass the faggot was too unwieldy once it had come under compression. The most successful way of creating a faggot was to lay a 3m line of twine on the ground. Lay the required amount of furze on top of this, which as a general rule stood about 1.5m off the ground. This part of the process was an adaptation of the traditional method of faggot making. It was necessary to reduce the overall mass of the material to reduce transport and environmental costs. Traditionally the furze was cut in a manageable armful and then tied with a green whip, possibly goat willow, perhaps in a similar style to how a bundle of willow rods are tied. My adaptation meant laying the fuzz outward at both ends to balance the shape to create a more symmetrical faggot. [This change to the dynamics of the traditional faggot was the main concession to the modern age the project made other than that of transportation]. A loop was tied at the end of the twine drawing the other end through. As the faggot tightened at the pull of the twine I placed my boot onto it to help shape and round of the faggot and to compress it further. Creating a tightly formed well shaped faggot was a really satisfying process. The ideal size and weight of the faggot being determined by whether or not it could be carried by one person.

The circular form of the work had another origin other than a reference to fuel storage. It was to do with the elements. I was interested to find out about the typical construction shape and techniques of building a furze rick. In book form I discovered little though my research was not exhaustive. In photographic form I discovered, thanks to the Old Cornwall society, one of a woman carrying a faggot taken from a rick at Dowran near St Just. In the background a shape not unlike a domed haystack stood. This was the only photographic record I could find of a rick. I found further information and help from Peter Dudley of the Historic Environment in an unpublished paper. It seemed natural to construct the work in circular fashion quite simply so that it could take on a strong wind from any direction deriving strength from its design. This is how and why I built the rick near Morvah knowing how the wind can pick up there. It was interesting to find that I had inadvertently re created the technique when discovering this research later on.

In a conversation with a neighbour after the burn, he told me of how he used to build a rick called a knee-mow. The size of faggot was relative to the growth available. 3 faggots were placed upright in the middle like a stook of corn. Then the faggot was laid furze on the outside stem to the middle. A complete ring was created and two further rings. These were laid tightly next to one another. You would then use your knees to compress the faggot - hence the name - on the next layer and so on. This would be about 6 yards across from one side of the circle to the other and flat on the top. This was remarkably similar in form to the rick we made at Morvah.

In a conversation with a neighbour after the burn, he told me of how he used to build a rick called a knee-mow. The size of faggot was relative to the growth available. 3 faggots were placed upright in the middle like a stook of corn. Then the faggot was laid furze on the outside stem to the middle. A complete ring was created and two further rings. These were laid tightly next to one another. You would then use your knees to compress the faggot - hence the name - on the next layer and so on. This would be about 6 yards across from one side of the circle to the other and flat on the top. This was remarkably similar in form to the rick we made at Morvah.

The height of the work was ideal to work with a ladder at [2.3m] without the necessity/hassle/expense of tower scaffolding. The lowest half of the work was built by school children [age range 10-15] as they wouldn’t have been allowed to work off the ground due to Health and safety reasons. The children were really good to work with and fun, interested people to have around. The quality of their work was good and didn’t need to be adjusted in any significant way – in fact they did too much on one day and I had dismantle some of it to ensure the next team had something to build. Much of the construction side of the project was held back to allow for participation. This was an unusual development which would normally be at odds with how a rick would have been built. However, developing a strong element of participation was one of the most important parts of the project.

In the middle of the lowest section and highest point of the work I left a temporary gap of 3m. I did this for two reasons. It was difficult to judge whether or not I had enough material and that being the tallest section would consume the most furze. I reckoned that I would be maybe 10 faggots short the amount that it would take to fill the gap. After a few calls to make sure I could get hold of some more furze cut around the same time I pressed on with constructing the second half. The other reason was that it acted as a fire break. In reality fire would more than likely have jumped that distance or at least the heat would have ignited it. But it seemed right to incorporate that that kind of thinking or approach in construction as it mirrored the procedure used in creating fire break control on heath land. As it turned out my estimations regarding material was bang on [to my relief] and instead I chose to use green furze in flower to emphasise this reference to a fire break.

The work was built on a sloping field of approximately 85 degrees [I:7m] The diameter of the circle was 15m across, the circumference being approximately 50m and the width of the walls were 1.80m. The internal supports were of 10mm steel reinforcing bars of which 200m were used. Four wooden posts were used to set the height of the work. Lines were then used to join each post at this height and then lined up by eye against the horizon of the sea. [This was something I used to do when setting the lines for stone hedging]. The highest level of the work was 2.3m and at the lowest 0.5m. I had intended to run the upper most and lowest part of the work straight into the ground but on experimenting I found it was too inconsequential as it meant just laying a few sticks on the ground. I raised it by 50cm to give it more body. This resulted in a slight sweep up ward from the mid way point. A doorway of 1m was left at the top of the work to access the space within. When people came to visit the work throughout the construction process and over the open weekend I would invite people in for look a round. It was very much like inviting people into your home for tea.

I had originally intended to make a completely sustainably resourced work.

It had to have a support structure of some kind inside it and for this I had planned to use thinnings from woodland management activity on the Penrose estate, Helston to create a wooden scaffolding around witch the work would be built. The more I addressed the issue of sustainability the more unattainable the concept appeared to be. I would need to travel to site using oil based fuel, as would the majority of every one else, and the transport of the materials would rely on it too. I decided to explore the contradictions of this as a more potent discussion point relevant to the concepts of the project. A sub-title for the project [‘Sustainable sculpture in an age of climate change‘] emerged during the development stage of the project and was part of this exploration. This was intended partly to be a question as much as a proclamation, and as mentioned previously, the inclusion of steel rods in stead of coppiced poles helped investigate this.

It had to have a support structure of some kind inside it and for this I had planned to use thinnings from woodland management activity on the Penrose estate, Helston to create a wooden scaffolding around witch the work would be built. The more I addressed the issue of sustainability the more unattainable the concept appeared to be. I would need to travel to site using oil based fuel, as would the majority of every one else, and the transport of the materials would rely on it too. I decided to explore the contradictions of this as a more potent discussion point relevant to the concepts of the project. A sub-title for the project [‘Sustainable sculpture in an age of climate change‘] emerged during the development stage of the project and was part of this exploration. This was intended partly to be a question as much as a proclamation, and as mentioned previously, the inclusion of steel rods in stead of coppiced poles helped investigate this.

When working as a stone hedger in south and west Cornwall I was continually presented with a chaotic mass of stone and earth out of which I was expected to create order. The satisfaction of creating a uniform structure that came out of a situation like this was enormously satisfying. I drew heavily upon these experiences for the skills to develop and create the work. I originally had intended to produce a form that referenced the architecture of the home or farmstead and its associated landscape features such as haystacks, but moved away from this to avoid what I perceived to be an encroaching link to paganism and the melodrama that this seemed to bring. My conceptual and research developments led me to consider more appropriate forms of architecture in contemporary industrial fuel storage as a reference point. Knowing what I would eventually produce would be a traditional rick [energy store] built in a contemporary form I was inspired by these large circular steel plate constructions. The fact that I wanted to also release the energy stored within the gorse through fire and witness its’ eventual transition to carbon emission was further underlined by the connection with the recent petrochemical fires at Buncefield in the south east. This was conceptually important in the development of a steel support frame for the work. It was born of a desire to see something in conceptual opposition [steel wreckage] to the projects ethos. Further to this I wished to attach the event to a particular event in the calendar. Having designed the project to be a performative and temporary work I wanted it to remain as a strong memory in the mind of the audience. Each time the audience experiences that event they would remember the work due to the projects association to it. Bonfire night, Christmas, winter solstice or New Year? They were all heavily laden with meaning and I feared that they might dominate the work. After closer and more realistic examination of the timescale of the project I began to favour spring equinox [but still too heavy with its’ own associations] but favoured the anomaly imposed on the beginning of British summer time [turning the clocks back/interfering with time] as the appropriate calendar event. This seemed a more mechanical response to the seasons than a naturally occurring development of cultural interaction.

I remember very clearly the site meeting that secured me the opportunity of presenting my work at Tremenheere. At this meeting with Neil Armstrong the director of Tremenheere, he related to me a tale about how he had invited Nick Serota to discuss the potential of the Tate’s involvement in the provision of a public work on the very site of the work I was proposing. Serota had suggested Richard Serra as the artist to do justice to the place. The involvement of Serra was out of the financial reach of that project and though many were interested nothing came of it. This story caught my imagination and idly resurfaced in my imagination from time to time during the project. I think this conversation became unintentionally influential in the eventual design. Later, by coincidence I went on to have a conversation with artist Rupert White on the evening of the burn. In this he commented on how sculptural the work was [which I think caught a lot of people by surprise] and reminiscent of early Richard Serra.

The taming of a wild material such as furze was an objective of the project. It came about through wanting to respond to the differences, sometimes extreme, in the types of environments I was dealing with. I adopted an anal retentive outlook and applied it to the construction and finish [tightly manicured] of the work. This referred to our dominance of nature. What I had by the end was a very strong sculptural form. If it had been simply a stack of faggots the impact of destruction would have been lessened. The laborious intensively managed nature of the work was evident. This way the wastage was heightened.

The taming of a wild material such as furze was an objective of the project. It came about through wanting to respond to the differences, sometimes extreme, in the types of environments I was dealing with. I adopted an anal retentive outlook and applied it to the construction and finish [tightly manicured] of the work. This referred to our dominance of nature. What I had by the end was a very strong sculptural form. If it had been simply a stack of faggots the impact of destruction would have been lessened. The laborious intensively managed nature of the work was evident. This way the wastage was heightened.

Once the faggots had arrived on site they lay in one solid mass at the top of the hill. As a way of limiting the damage of a potential arson attempt I spread these out around the edge of the 15m circle I had marked out. I felt very exposed and vulnerable during this stage. It was later remarked how it resembled a hill fort. I did actually feel more secure and confidence began to grow once the walls had begun to take shape. Viewing the work laid out on the ground from a distance at the gardens gates it cut an impressive shape on the hill. At this stage, flat packed, it was approximately 60m across. Here a passing moment of doubt set in regarding whether or not I could pull it off as what I was now intending to build seemed to be in direct competition with the landscape - I felt it was in danger of being swallowed up whole by it. I also knew it was about to become half the size. In reality the work couldn’t even begin to compete with the size of space it was in when viewed fro a distance. I just had to wait and see and have faith in my ideas.

The conversations that took place throughout the project, whether in the harvesting stage or at Tremenheere, with the steady flow of passers by became an interesting and important part of the projects development. It enabled me to focus on the less physical side allowing this to develop through discussion of the more conceptual elements. In addition to this were the community events, the reactions to the heath land environment and in the harvesting and making of a large scale sculptural work in the grounds of a sub tropical garden. The differences in response were interesting too. The children reacted and explored the work very playfully and physically, the adults being generally more reserved reacted to its form and conceptual element. For example when harvesting at Morvah in West Penwith the children used the harvested furze as a trampoline as seen on the project poster. This part of Cornwall is famous for its lack of trees. Some of these children have hardly ever climbed a tree and it seemed that this was a natural replacement - despite the pain! Battle re-enactment scenes also occurred and by creating toys out of the discarded furze stems, brought Pokemon inspired creatures to life

From the beginning Neil Armstrong, the director of Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens, had been very supportive of the project and helped me in whatever way he could. But importantly I was left alone to develop the project. Although Tremenheere is developing a name for itself as a venue for environmental art it is not, as yet, open to the public on a regular basis. The fact that Neil opened the garden especially to coincide with the burn event was very much appreciated.

The Guys a farming family from Morvah, involved from the very beginning in not only the harvesting but the construction as well. They were fascinated by how I had taken an unforgiving natural material from a wild environment and brought it to a place with a parkland feel to it and how I had handled and tamed it. On there final visit to the work to assist in the final stages of construction they began to see other uses for it aside from fuel. One idea I that I found of interest was a proposal to use it as a wind break as dead hedging material to protect less hardy crops. This would then be recycled as fuel when the growing season was over. Also a crofting couple from Kelynack helped me clear furze from a would-be vegetable plot.

For the last section of the work I had decided to use green furze that was in flower. I cut this with the help of Dave Slater, a green woodworker, from his small holding near Gulval. Whilst cutting the furze from the sides of the rides in his tree plantations, Dave told me of an engraving he had seen showing how the Armada Beacons were made. These were built out of furze around a wooden pole (later removed to create a chimney inside it) and based on the same principles as a pine cone. These were 25ft tall with the fuzz laid outward, and kept dry by covering with a tarpaulin. When lit, the need here was intensity of light and not heat; the flames reached a 100 ft in the air. It was anecdotes like this that enriched the project and extended its boundaries. It helped me understand the role and importance of documentation in its own right and underlined the relevance of incorporating this as a bona fide part to CUT/STACK/BURN. Further underlining this element of the project was how it took on an archaeological leaning. After the burn the unpicking of the evidence became a forensic process relearning and reliving the recent past history of the project.

The support in kind from various individuals and organisations was fantastic. Without the support of these, particularly from ACE, it simply would not have come to fruition. The National Trust also stands out here as not only being very supportive on a practical level but also because of how they really got into the spirit of the work. From the cutting of the furze to the help on the day for stewarding and providing the event equipment was brilliant. The countryside manager even made a special visit to lend a hand in last stages of the work. When I set fire to the work I asked the warden who had worked and liaised with me on the cutting and transportation of the furze to join me in the last performance of the project. We did this using the same equipment [flame retardant overalls and gas weed burners] as they would when they are using burning as a tool for heath land management.

Monday, 26 March 2007

cut/stack/burn - the video

I have alot to do before I'll be able to show the video footage I took but in the meantime you can see Rupert Whites' youtube video at www.artcornwall.co.uk in the exhibition section. It is a good document and captures the various elements well. Thanks to everybody who helped me achieve what I did, those who have followed the plot thus far and those turned out to see the final stage...your response was amazing...Bruce Davies

Sunday, 18 March 2007

what a waste...

Now that the work is finally taking shape and the passing influx of visitors [e.g. lots of walkers form the St Micahels way] is increasing so are the chats/conversations/debates about the burning of work rather than the concept behind it. The general response is that it's a bit sad to see it destroyed ['a waste of an art/work']. Most, feel they would like to see it stay standing and feel it that it is shame to see it burnt in such a frivolous way after the considerable work done by many. I have some sympathy here [I like what I have created too!] as this the point I have been working toward and my feelings are that it would only be half the work if it was left standing. It truly is a waste of art - but my agreement ends there. By destroying a hard won fuel/energy source it underlines in a similar way to how we use energy. The work sets out to create wastage in order to engage with the subject of wastage itself. It creates pollution to engage with the creation of pollution. By destroying something that is cared in for someway, I hope to underline or raise questions about the relationship we have and values we assign to the energy/resources we use.

Thursday, 15 March 2007

school visits

This week saw the influx of very welcome and enthusiastic help from St Just Primary school and Mounts Bay secondary school Penzance. The young students never turned a hair at the prospect of using such an unforgiving material and good fun to have around. St Just y6 completed the upper left section followed up by Mounts Bay with the middle to upper on the right. the methodic and careful approach by y10 Mounts bay was really good to see and showed what young adults are relly capable of given the chance to be hands-on out of the class room. This hive of activity was matched by the speed and determination of the industrious y6 team form St Just earlier in the week. Well done and thanks for the effort, it was fantastic.

Tuesday, 27 February 2007

rumble neck halfhorn finds a new home

today gorsey-horsey as he came to be known was renamed at our house as 'rumbleneckhalfhorn' and given his first taste of comfort on the train set box on his very own bed. this sort of stuff is an unexpected and fun side to the work so far. we had gorse trampolines at the start furzey arrow trails and now this...bring it on

Monday, 26 February 2007

fire symbolism

I couldn’t agree more with you about the importance of exploring our relationship with the landscape through making art that interacts with it rather than just depicts it. What about the religious symbolism of fire: that’s the thing that I find most interesting... [Rupert White - artcornwall]

Early on I wanted to Piggy-back my work on to an already existing cultural event and try to melt my work into the memory of the audience. Events like bonfire night/solstice/new year were considered. But I had to be careful in that I didn't want the work to be swamped by the associations of it. As the proposal for the project developed and the time line for it became extended I started looking to the New Year and further calendar dates. I new I could be ready Feb/march and focused on spring equinox. But the pagan side of things was a bit too prominent and so I chose to use the eve of the beginning of British summer time instead. I was much happier about this as it is in itself an anomaly of nature [turning back time] in a similar way to the events happening through climate change. Fire is an extremely evocative material to work with and it is no wonder religions use it to good effect – hell-fire-damnation/wicker man etc. Though aware of the religious connotations of fire it was more a parasitical relationship than meaningful one.

Early on I wanted to Piggy-back my work on to an already existing cultural event and try to melt my work into the memory of the audience. Events like bonfire night/solstice/new year were considered. But I had to be careful in that I didn't want the work to be swamped by the associations of it. As the proposal for the project developed and the time line for it became extended I started looking to the New Year and further calendar dates. I new I could be ready Feb/march and focused on spring equinox. But the pagan side of things was a bit too prominent and so I chose to use the eve of the beginning of British summer time instead. I was much happier about this as it is in itself an anomaly of nature [turning back time] in a similar way to the events happening through climate change. Fire is an extremely evocative material to work with and it is no wonder religions use it to good effect – hell-fire-damnation/wicker man etc. Though aware of the religious connotations of fire it was more a parasitical relationship than meaningful one.

Sunday, 25 February 2007

from artcornwall

Bruce: talking of smoke can you explain a bit more on the forum about whether cut stack and burn will be helpful or harmful to the environment: or may be that’s not the point...[Rupert White]

To be helpful or harmful? Well I would say that by being harmful I hope to be helpful. There a few points that this project circum-navigates…

I will cause pollution through burning the work [though not very much in comparison with oil, but atmospheric pollution it is]. There is little of what we do that does not have some consequence or other for the environment. But there are clearly both acceptable and unacceptable limits for the impact of our daily actions. The work and the burning of it, seeks to underline the inseparability of cause and effect in our lifestyles. The creation of smoke is a visual expression of this.

I have an interest in using sustainably resourced natural material derived from land management cycles - such as furze – informed by my art practice and nature conservation experience. I particularly wanted to use a material that was a by product of such a process that had not been created especially for my work, a material that had been cut by hand [machete] and not by power tool.

I have set out to create an interactive project with an audience using the landscape as a platform for its ideas while avoiding pictorial representation. In this case I have looked at what is happening to the landscape and have responded using visual methods such as performative re-enactment [cutting] and hands-on participation [stacking] with unconventional material and contexts that use materials to examine issues not traditionally associated in the realms of landscape art such as sustainability. This has entailed the gathering of material from the landscape in the preparation stages, to witnessing the transition from material mass to constructed form through performative events played out in the tamed environment of a subtropical garden. The final stage of the project, when the project is at its ‘zenith’, will be to release the energy stored in it. The work will be set alight as furze traditionally was but not as a domestic fuel source. The burning of the work serves a practical purpose – to see the transition of energy stored in the material released into smoke/gases and heat. The releasing of this energy by combustion is effortless – and should be very quick. This conceptual action references the pressing of a button or flicking of a switch. This quick, easy and effortless familiarity is how the vast majority of us consume energy. To have taken so much time and effort to harvest an energy source and painstakingly build something only to destroy it the moment it has been created, sends echoes to me about our flippant regard to energy use.

We generally have no direct experience of the harnessing of energy we use. This is in direct contrast to the experiences of the people involved with the CUT/STACK/BURN project which sets out, in part, to illustrate the effort involved in procuring your own energy source.

In my practice an awareness of society’s relationship with natural resources and our collective use of energy have emerged in my work and I am eager to explore how a visual interpretation of this might proceed. How contemporary artists can engage in a relevant way with the environment, landscape or whatever name you would call it, given the legacy that, on a regional level at least, still appears to be encumbered by pictorial representation is of interest to me. Often, when the use of landscape is used as subject matter in painting for example, a principle theme -the evocation/translation of beauty – becomes an obsession. But is that the only way to engage with the landscape? What does that tell us about it? Is that all it is a thing of beauty? I believe this is not only a limited and blinkered view but also a dangerous one. When art lacks meaning it becomes decoration. The same happens when the landscape is treated in a similar way. It becomes a product to be packaged, to be manipulated and marketed solely as a place of leisure. Our relationship with it becomes diminished and superficial. I think that ‘pretty’ needs to be taken out of the picture completely. The pictorial representation of the landscape holds no interest for me but a work that looks beneath the surface of what it is and means to the people who use it and tries to address the issues it faces appears to me to be a far more relevant way to engage with it.

To be helpful or harmful? Well I would say that by being harmful I hope to be helpful. There a few points that this project circum-navigates…

I will cause pollution through burning the work [though not very much in comparison with oil, but atmospheric pollution it is]. There is little of what we do that does not have some consequence or other for the environment. But there are clearly both acceptable and unacceptable limits for the impact of our daily actions. The work and the burning of it, seeks to underline the inseparability of cause and effect in our lifestyles. The creation of smoke is a visual expression of this.

I have an interest in using sustainably resourced natural material derived from land management cycles - such as furze – informed by my art practice and nature conservation experience. I particularly wanted to use a material that was a by product of such a process that had not been created especially for my work, a material that had been cut by hand [machete] and not by power tool.

I have set out to create an interactive project with an audience using the landscape as a platform for its ideas while avoiding pictorial representation. In this case I have looked at what is happening to the landscape and have responded using visual methods such as performative re-enactment [cutting] and hands-on participation [stacking] with unconventional material and contexts that use materials to examine issues not traditionally associated in the realms of landscape art such as sustainability. This has entailed the gathering of material from the landscape in the preparation stages, to witnessing the transition from material mass to constructed form through performative events played out in the tamed environment of a subtropical garden. The final stage of the project, when the project is at its ‘zenith’, will be to release the energy stored in it. The work will be set alight as furze traditionally was but not as a domestic fuel source. The burning of the work serves a practical purpose – to see the transition of energy stored in the material released into smoke/gases and heat. The releasing of this energy by combustion is effortless – and should be very quick. This conceptual action references the pressing of a button or flicking of a switch. This quick, easy and effortless familiarity is how the vast majority of us consume energy. To have taken so much time and effort to harvest an energy source and painstakingly build something only to destroy it the moment it has been created, sends echoes to me about our flippant regard to energy use.

We generally have no direct experience of the harnessing of energy we use. This is in direct contrast to the experiences of the people involved with the CUT/STACK/BURN project which sets out, in part, to illustrate the effort involved in procuring your own energy source.

In my practice an awareness of society’s relationship with natural resources and our collective use of energy have emerged in my work and I am eager to explore how a visual interpretation of this might proceed. How contemporary artists can engage in a relevant way with the environment, landscape or whatever name you would call it, given the legacy that, on a regional level at least, still appears to be encumbered by pictorial representation is of interest to me. Often, when the use of landscape is used as subject matter in painting for example, a principle theme -the evocation/translation of beauty – becomes an obsession. But is that the only way to engage with the landscape? What does that tell us about it? Is that all it is a thing of beauty? I believe this is not only a limited and blinkered view but also a dangerous one. When art lacks meaning it becomes decoration. The same happens when the landscape is treated in a similar way. It becomes a product to be packaged, to be manipulated and marketed solely as a place of leisure. Our relationship with it becomes diminished and superficial. I think that ‘pretty’ needs to be taken out of the picture completely. The pictorial representation of the landscape holds no interest for me but a work that looks beneath the surface of what it is and means to the people who use it and tries to address the issues it faces appears to me to be a far more relevant way to engage with it.

Saturday, 17 February 2007

Friday, 16 February 2007

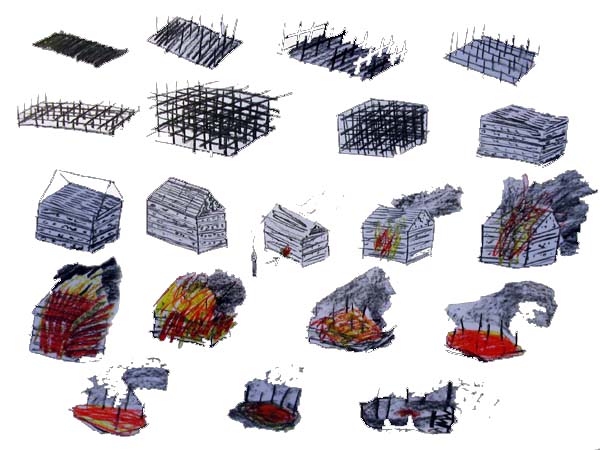

The form of the construction has now moved on a fair bit since its first conception. Originally I had been interested in forms that referenced the domestic home where we expend most of our energy and also the architecture of the farm environment. I looked at barns/yards/haystacks/enclosures etc which in turn led me to consider the more modern intensive architecture of farm storage facilities such as slurry pits/containers/silage clamps etc, and finally to focus on large scale industrial circular fuel storage tanks [given that the furze rick is in itself a fuel store] for oil/gas/petrol and so on. The dimensions of the work will be built as a ring in the region of 20m in diameter and 2.5m in height at its highest point. It will be built on a sloping field over looking Mounts Bay. The interior of the work will be accessible through a narrow opening at the upper most part of the circle.

My practice is concerned with examining ways in which contemporary art can engage the landscape in a valid interactive discourse not based solely on a one way observational relationship. It is an exploration of the relationship between artist and environment and the how the sociological landscape figures in contemporary art, by looking at the artists’ use of the landscape as a source of inspiration. An important part of this is the annexation of the landscape as product, cultural change towards it and the potential for disenfranchisement that may incur. My interests and inevitable enquiries, led to a variety of social topics concerned with apparent schisms in Cornwall’s resident community’s needs and desires contrasted against those of a transitory tourist population and a landscape under pressure. The way these needs play out and the friction that ensues with each user group is of significant interest. This, in connection with the history of Cornwall’s past and present art community, presented a series of questions for me. How does a practising artist, responding to the landscape as a source of inspiration, fit into Cornwall’s contemporary cultural context? Are the present socio-economic situations, and the issues and cultural practices that change it more of a pressing concern than the depiction of the landscape itself? Could a visual interpretation of the shifting sociological importance of the landscape be of more relevance than pictorial representation? How can this proceed?

RE: cornishaman article

Well the carbon emission thing got a bit lost in the mix. There is a crucial word missing from the text. It should read 'furze smoke is not as carbon-producing like fossil fuels'. Its an important point to the work that pollution is caused by the burning of the work. It emphasises the fact that little of what we do is free from any environmental impact. Although I have gone out of my way to create a work that uses sustainable materials that are already part of an existing process, the use of diesel powered transport to move the material conflicts with the projects sub title 'sustainable sculpture in an age of climate change'. Which is meant to be as much a question as a proclaimation.

RE: cornishman article

It is about our attiude to energy but its also about how as artists we interact with the natural environment too. Its often the case that when working in issue based fields that the art becomes less than central - no matter- but at the heart of this visual debate is an attempt to move away from pictorial representation when using the landscape as subject matter or inspiration and begin an investigation into how art can use the landscape in a more relevant way. The 'pretty' needs to be removed from the landscape/land art 'picture' altogether.

Wednesday, 31 January 2007

Preamble to cut/stack/burn

Since finsihing the fine art course at University College Falmouth in the summer of last year I have spent my time developing the frame work for an artist residency with the National Trust. It came at a time when, given our geographical distance from everywhere, I was beginning to feel fairly isolated. I knew if I were to stay in Cornwall I would have to adopt a fairly innovative approach in my art practice. I set about to capitalise on Cornwall’s geographic isolation by using the landscape, so often referred to in artists work in Cornwall, to address subjects that were important to me. Prior to UCF I worked in nature conservation before returning to study the remainder of my fine art degree that I had left in late1998 [brought about by a severe hearing loss].

On many occasions during my career in nature conservation I had found myself approaching and trying to tackle projects from a creative perspective. This wasn’t always practical and left me feeling that in some cases much more could be achieved if we were able to blur the boundaries between art and non-art disciplines and work more closely when working toward similar/connected goals.

The ideas I had through this time involved amalgamations of working processes and creative solutions. These were mostly time consuming and laborious visual proposals that did not fit into the conventional budget constraints of a nature conservation organisation for example. Whilst at UCF the dynamics of my course and home life meant that they had to be shelved further still. In this time I worked sporadically on the conceptual nature of these ideas.

On leaving UCF I began to develop these ideas afresh and saw that a residency with the NT as being the best way to pursue them. The residency lasts for a year and CUT/STACK/BURN is the first of four seasonally based projects responding to the properties on the lizard and Penrose estate, Helston.

On many occasions during my career in nature conservation I had found myself approaching and trying to tackle projects from a creative perspective. This wasn’t always practical and left me feeling that in some cases much more could be achieved if we were able to blur the boundaries between art and non-art disciplines and work more closely when working toward similar/connected goals.

The ideas I had through this time involved amalgamations of working processes and creative solutions. These were mostly time consuming and laborious visual proposals that did not fit into the conventional budget constraints of a nature conservation organisation for example. Whilst at UCF the dynamics of my course and home life meant that they had to be shelved further still. In this time I worked sporadically on the conceptual nature of these ideas.

On leaving UCF I began to develop these ideas afresh and saw that a residency with the NT as being the best way to pursue them. The residency lasts for a year and CUT/STACK/BURN is the first of four seasonally based projects responding to the properties on the lizard and Penrose estate, Helston.

Furze was harvested from heath land [or rough ground] and was once a primary source of domestic fuel for cooking and heating in west Cornwall. The management of furze in this way was part of an ancient and traditional method that ensured extensive grazing for livestock. The cutting of furze provided a varied mix of plant and grasses which thrived on this management. It was also used as an industrial fuel used in tin smelting and for burning in lime kilns.

Source [P. Dudley, Historic Environment Service

http://www.cornwall.gov.uk/index.cfm?articleid=28957]

Source [P. Dudley, Historic Environment Service

http://www.cornwall.gov.uk/index.cfm?articleid=28957]

Harvesting at Coverack

After lots of cutting the National Trust volunteers and staff, have cut lots of furze ready to be bundled into faggots. This has been part of their heath land management for this area and provides the main bulk of CUT/STACK/BURNs’ material. We are doing this now and have already got 50 or so faggots of about 8ft in length and 3ft wide. The access is tricky as it is a fair way from the nearest track so there is a fair amount of carrying to come. . I estimate that we will need something like 150 to complete the installation at Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens.

Weather report: [I am an anorak]

It’s been really excellent weather this week! [ talking about and watching the weather has become very obsessive] no wind - still in fact- a rare treat and no rain – which is good as the ground won’t get so churned up when we take the faggots out. It’s been warm too, I saw my first Red Campion today and the furze is getting ready for a vibrant display.

Weather report: [I am an anorak]

It’s been really excellent weather this week! [ talking about and watching the weather has become very obsessive] no wind - still in fact- a rare treat and no rain – which is good as the ground won’t get so churned up when we take the faggots out. It’s been warm too, I saw my first Red Campion today and the furze is getting ready for a vibrant display.

This week saw the HEATH project [www.theheathproject.org.uk] joining Arts Council England and the National Trust as funders for the project.

This is an extract from their website -

The North-West Europe heathland landscape is of great ecological, economic and cultural significance, but is in long-term qualitative and quantitative decline. The loss of direct economic and cultural links that formerly sustained heathland is a major cause of its decline. The HEATH (Heathland, Environment, Agriculture, Tourism, Heritage) Project aims to re-establish the social and economic integration that was once associated with heathland environments. This will be achieved by reintroducing and improving habitat management practices and by communicating and promoting heathlands as a potential valuable resource with a valuable historical context. The key objective of the HEATH project is to develop a management model and tool kit that will establish and help guide future heathland management and be applicable across the NWE heathland landscape.

The HEATH project is made up of many international organisations. This support will be mutually useful in promoting the work and extending the audience of CUT/STACK/BURN and importantly that of the HEATH project and its’ ‘Heath Fest’ in September 2007. [For more info please visit their website]. The linking of different organisations working with similar issues is of interest to me as it enables the work to travel into different arenas and work more effectively.

This is an extract from their website -

The North-West Europe heathland landscape is of great ecological, economic and cultural significance, but is in long-term qualitative and quantitative decline. The loss of direct economic and cultural links that formerly sustained heathland is a major cause of its decline. The HEATH (Heathland, Environment, Agriculture, Tourism, Heritage) Project aims to re-establish the social and economic integration that was once associated with heathland environments. This will be achieved by reintroducing and improving habitat management practices and by communicating and promoting heathlands as a potential valuable resource with a valuable historical context. The key objective of the HEATH project is to develop a management model and tool kit that will establish and help guide future heathland management and be applicable across the NWE heathland landscape.

The HEATH project is made up of many international organisations. This support will be mutually useful in promoting the work and extending the audience of CUT/STACK/BURN and importantly that of the HEATH project and its’ ‘Heath Fest’ in September 2007. [For more info please visit their website]. The linking of different organisations working with similar issues is of interest to me as it enables the work to travel into different arenas and work more effectively.

Cutting and stacking at Keigwin farm

The furze harvesting started with the Guy family and friends at Keigwin farm on the north coast of West Penwith this week. The Guy family share grazing on the heath above their farm and they are trying to bring it back in as extensive rough grazing. After a few days cutting we moved the furze by trailer back to the farm where the ‘ricking’ commenced. There isn’t much in the way of photographic records of furze in ricks [stacks] generally. For our purposes the constraints of the mow hay and nearby barns determined the size, shape and position. A circular form was favoured as this allowed us to interlock the stems, thus holding each other in place, safeguarding against the strong wind experienced on that coast line. From a picture of a furze rick at Dowran, St Just that I have seen [C18] the rick appears to have been covered on the top by a canvas tarpaulin and covered in an old fishing net and weighed down. Once the top of the rick has been rounded off [its flat at the present - awaiting more material] it will be interesting to see how this fairs, by comparison, in the next gale. [I’ll try to get permission to post the photo on the blog so you can see it yourself]. One of my interests is how we adapt old techniques to suit new circumstances. So from this point I don’t intend to replicate a particular rick structure but to fit it to the needs of the project, though in principal I would imagine it remains very much unchanged.

The children approached the harvesting and stacking with gusto and later enjoyed the rewards of the hard work by turning the rick into a natural trampoline. It reminded me of tree climbing, springing about on the branches. I have no doubt this was a practice that use to happen in days past. It was good to see that no one particularly bothered about the scratches endured throughout the day and was an enjoyable way of illustrating how energy was once sustainably produced.

The children approached the harvesting and stacking with gusto and later enjoyed the rewards of the hard work by turning the rick into a natural trampoline. It reminded me of tree climbing, springing about on the branches. I have no doubt this was a practice that use to happen in days past. It was good to see that no one particularly bothered about the scratches endured throughout the day and was an enjoyable way of illustrating how energy was once sustainably produced.

Tuesday, 16 January 2007

Press release

CUT/STACK/BURN – A prickly kind of heat adds to climate change debate

Visual Artist Bruce Davies is to build a public sculpture out of furze at the sub-tropical Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens, Penzance…and then set fire to it! He will be gathering the furze during February and constructing a large installation with it over a 3 week period in March.

The culmination of the project, entitled CUT/STACK/BURN, coincides with the start of British summer time and is a specific reference to our relationship to energy use. On the 24th of March the sculpture will be burnt at a public event, not as a domestic fuel as furze traditionally was, but as a frivolous action that reflects on our attitude to energy consumption and finite natural resources.

Bruce, who is funded by Arts Council England’s Grants for the arts programme, has developed this project in collaboration with the National Trust as part of his year long artist residency based on the Lizard and Penrose estate Helston. CUT/STACK/BURN is motivated by the cultural history of lowland heaths and the working processes that occur there. The project focuses on using sustainably resourced natural waste products from heath land management on the Lizard and Penwith to develop a visual work about the large scale absences of such approaches in the management of land and natural resources.

In February the furze will be cut and stacked into ricks at various rural locations for drying and then removed at a later date to be built into a large sculpture at Tremenheere. The harvesting of the material is a collaborative effort between the artist, landowners, conservation groups and local communities. In March, school children and volunteers will be working as a team with Bruce as lead artist to help bind and shape the furze into to the main sculpture.

“Furze cutting used to be part of a traditional sustainable cycle of land use; it was a major source of fuel in Cornwall and else where,’ says Bruce. ‘I am using this as an example of good practice in contrast to how we produce and use energy today. We haven’t had to go out to cut and collect gorse on a wind blasted heath to power our ipods, washing machines or whatever. If we did, rather than press buttons, perhaps we might be more thoughtful about how we use energy. In a symbolically frivolous act, after months of laborious cutting, stacking and building I am going to burn the furze sculpture to the ground.’

Ends

Visual Artist Bruce Davies is to build a public sculpture out of furze at the sub-tropical Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens, Penzance…and then set fire to it! He will be gathering the furze during February and constructing a large installation with it over a 3 week period in March.

The culmination of the project, entitled CUT/STACK/BURN, coincides with the start of British summer time and is a specific reference to our relationship to energy use. On the 24th of March the sculpture will be burnt at a public event, not as a domestic fuel as furze traditionally was, but as a frivolous action that reflects on our attitude to energy consumption and finite natural resources.

Bruce, who is funded by Arts Council England’s Grants for the arts programme, has developed this project in collaboration with the National Trust as part of his year long artist residency based on the Lizard and Penrose estate Helston. CUT/STACK/BURN is motivated by the cultural history of lowland heaths and the working processes that occur there. The project focuses on using sustainably resourced natural waste products from heath land management on the Lizard and Penwith to develop a visual work about the large scale absences of such approaches in the management of land and natural resources.

In February the furze will be cut and stacked into ricks at various rural locations for drying and then removed at a later date to be built into a large sculpture at Tremenheere. The harvesting of the material is a collaborative effort between the artist, landowners, conservation groups and local communities. In March, school children and volunteers will be working as a team with Bruce as lead artist to help bind and shape the furze into to the main sculpture.

“Furze cutting used to be part of a traditional sustainable cycle of land use; it was a major source of fuel in Cornwall and else where,’ says Bruce. ‘I am using this as an example of good practice in contrast to how we produce and use energy today. We haven’t had to go out to cut and collect gorse on a wind blasted heath to power our ipods, washing machines or whatever. If we did, rather than press buttons, perhaps we might be more thoughtful about how we use energy. In a symbolically frivolous act, after months of laborious cutting, stacking and building I am going to burn the furze sculpture to the ground.’

Ends

Tuesday, 5 December 2006

In early February the harvesting of furze will begin in earnest. This will be done with the assistance of conservation agencies/volunteers and farmers. The furze will be stacked into ricks [stacks] to dry and later transported to Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens, Penzance. In march the construction of an installation will begin with help form a number of schools. It will be a team effort of carrying, bending and binding the furze into the art work and will resemble the outline of agricultural buildings and related landscape features like haystacks. In the mean time through December and January I'll be constructing furze ricks on various harvesting sites spread across the Lizard and Penwith. The position of these will be announced as the project progressess and will be able to be seen on site and via images on this blog.

Poor mans holly

While researching the background about the cultrual uses for furze and lowland heaths I came upon the 'recipe' for Poor mans holly. These were used as a substitute for holly wreaths at Christmas. Without wanting to sound too Blue Peter-ish - it's really easy to do and very effective!.. and free...and prickly. All you need is the determination to go out on a wind blasted heath and a pair of secatares. Once you've got the brute home wet it under the tap, give it a quick knock to shake the big drips off and sprinkle white [not wholemeal] flour over it through a sieve, until the required 'I've been hit with an avalanche look' has been achieved. Then go out and find some red berries and stick them on. Sorted! A traditional and sustainably sourced Christmas decoration!

Wednesday, 29 November 2006

Cornwall’s natural environment, geographical position and cultural history are distinctive. I took these features as a starting point in developing a year long residency with the National Trust on the Lizard and on the Penrose estate, Helston. The project is motivated by the cultural history of lowland heaths and the working processes that occur there. I have an interest in using sustainably resourced natural material derived from land management cycles - such as furze – informed by my experiences in art and nature conservation over the last decade. During this time an awareness of society’s relationship with natural resources and our collective use of energy have emerged in my work and I am eager to explore how a visual interpretation of this might proceed. I am equally interested to understand how contemporary artists can engage with the environment, or landscape, given the legacy that, on a regional level at least, still appears to be encumbered with issues of pictorial representation.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

mini beasts

cross section

struts

14

![i survived an assalut by a deadly [natural] weapon and lived to tell the tale](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/2561/191242230969139/410/85448/gse_multipart25569.jpg)